What does a giraffe’s gestation and the current Yield Curve inversion have in common? Both are 13 months in the making. Before you hit delete, it may be worth exploring its importance.

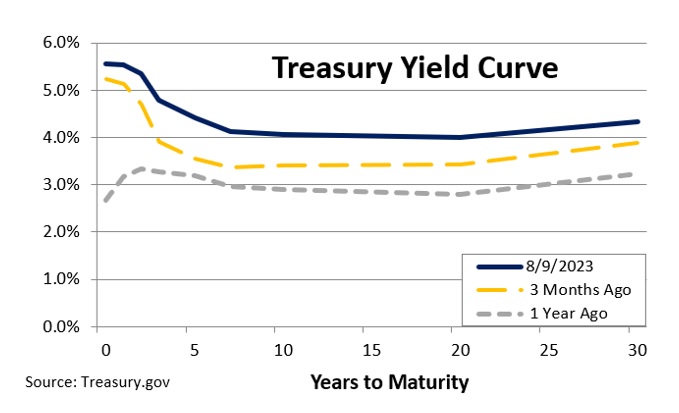

Yes, the Yield Curve is one of those geeky investment metrics affixed to portfolio managers’ computer screens. The Yield Curve is not as esoteric as it seems. It is simply a chart of bond yields laid out by maturity. With one glance, the Yield Curve displays expected yields. For example, a 10-year bond will yield about 4.0%, while a 2-year bond would yield about 4.8%. Simple enough. For relevance, the Yield Curve from three months ago and one year ago are also charted.

Though the Yield Curve is a simple plotting, the contour can be profound. Under normal circumstances, the Yield Curve is positively sloped, meaning longer bonds have higher yields. This should make intuitive sense. Lenders should receive compensation (yield) based on risk incurred. The longer the period, the higher possibility risks will be incurred. Analyzing the curve’s shape and slope communicates broad economic expectations.

Over the past 13 months, the Yield Curve has been inverted. As you can see from the chart, the near-term maturities offer higher yields than the longer maturities. Seems odd. Why would short-term maturities yield more than long-term maturities? In short, the market sees more risk in the near-term. Also, The Federal Reserve (Fed) has purposely raised near-term rates to slow the economy in its attempt to conquer inflation. Yield Curve inversions are very irregular and don’t tend to last more than a few months. However, the current inversion is 13 months long and counting1.

Yield Curve inversions hurt banks. Normally, banks earn money from the difference between what is lent to people and businesses versus what banks pay to depositors. Since deposits can be demanded at a moment’s notice, they can be thought of as renewing one-day deposits. During normal times, banks earn enough to thrive. However, during Yield Curve inversions, banks are subject to losses. To mitigate losses, banks curtail lending. This is where business (especially small business), workers and the economy get hurt.

Small business is the growth engine of the economy, yet small business needs capital or loans to expand, take on new projects, and hire employees. If banks are reluctant to lend, business is starved of needed capital. Stunted business plans mean fewer projects, curtailed expansion and fewer hires ultimately slowing the economy. Don’t blame banks. The Fed is deliberately exploiting this relationship to address inflation.

With inflation grinding closer to its target range, the Fed should recognize the typical delayed effect of its rate increases. The majority of the rate hikes still have not been fully digested by the economy. The longer the Yield Curve inversion exists the higher recession risks compound. Geeky investment measures are often ignored by most, but the Yield Curve is screaming “caution ahead.” Enjoy these last days of summer.

1U.S. Treasury

CRN-5881635-081523

Recent Comments