With tariffs dominating the headlines again, we thought it would be worth revisiting this topic. Headlines have inflamed the inflation and trade war debates. Tariffs and the threat of tariffs have multiple objectives that are not always tied to the tariffed product. Just this week, Mexican President Sheinbaum and Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau agreed to assist with border security in exchange for a 30-day delay of tariffs.

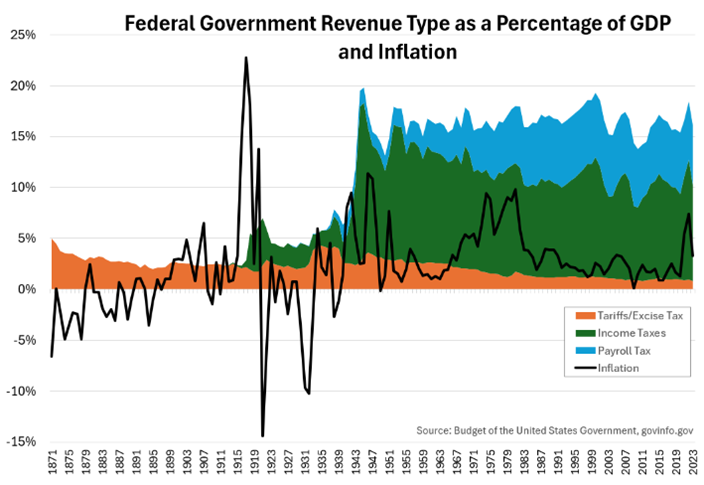

Tariffs are not a new phenomenon. In fact, tariffs have been around longer than income and payroll taxes. Tariffs were the primary federal government revenue stream until 1913 with the passage of the 16th Amendment1. Payroll taxes were introduced during the Great Depression to fund Social Security, providing a social safety net.

Tariffs are designed to make foreign goods and services more expensive, encouraging domestically produced goods and services. On the surface, this sounds like inflation via higher prices on tariffed foreign products or a shift to higher-priced domestic goods. To some degree, this logic is sound. However, the world is far more dynamic than a binary choice. The market of goods and services includes competition (think different TV makers. At the end of the day, a TV is a TV), substitute goods (think transportation via car, motorcycle/scooter, bicycle, public transport, taxi/uber, etc.), or foregoing purchases all together (think postponing a car, computer, or clothing purchase).

A bit of history. 2002 steel tariffs resulted in steel inflation for the first nine months of 20022. Clear evidence that tariffs resulted in a one-time price increase, not ongoing inflation. The market adjusted to a supply shortfall, similar to the COVID supply chain effects that we lived through a few of years ago. 2009 tire tariffs initially seemed to result in higher prices. However, a deeper dive reveals the higher prices were due to errant weather flooding in Thailand and halting rubber tapping2. (Thailand accounted for 31% of global rubber supplies.2) 2018 Chinese pork tariffs were followed by a global drop in pork prices2. In short, the Chinese tariffs resulted in lower global pork demand, which raised pork stockpiles and resulted in falling pork prices.

Tariffs are most often proposed to thwart other risks and threats. In current times, the media’s myopic one-step tariff analysis unfortunately missed the larger objective of boarder security, illicit drug enforcement and international trade policy. In 2020, the U.S. threatened wine tariffs to counteract France’s “digital services tax,” targeting U.S. technology companies3. After careful consideration, France decided not to proceed with their “digital services tax” resulting in no tariff or tax being applied on either side.

The call for tariff induced inflation or detrimental trade wars may be premature. The historical record does not support either as an imminent conclusion. The nature of economics and geopolitics is its everchanging dynamism. Just this week, Sunday’s tariff “certainty” was postponed due to Mexican and Canadian concessions. There is more to the tariff story than prognosticators portend. Even if they do not agree with the objectives, announcing possible outcomes as forgone conclusions may be unwise.

Recent Comments